OCTOBER 28th, 312AD

The Battle of the Milvian bridge is one of the defining battles in world history. Fought by the Roman Emperor Constantine against a rival claimant to the throne, the usurper Emperor Maxentius, the battle ultimately resulted in the conversion of Constantine to Christianity. I cannot emphasize enough the significance of this event in world history. With Constantine’s conversion came the end to persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, the founding of the Eastern Roman capital of Constantinople, and the Christianization of both the Romans and their barbarian enemies.

The rapid conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity still stands as one of the greatest surprises in history. Christianity, diametrically opposed to almost every value espoused by Roman paganism and the Roman state, quickly gained a foothold in the Empire in the early 300s AD, during the reign of Constantine. Within a hundred years, the percentage of Christians in the Empire increased from approximately 10% to nearly 95% of the total population. While sudden and unexpected, this would prove to be a lasting change, and it had a profound effect upon the western world. As the traditional Roman values dropped away, those of personal glory in battle, aspiration to material wealth, and a strong concept of civic duty, the Roman world changed, at first gradually and then quickly, and finally came tumbling down into the chaos of the dark ages.

In this post, I will dive into the events leading up to the eventual conflict between the rival Emperors, the course of the battle itself, and the ramifications of this event that persist until this day. To begin with the story of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, one must go back a century earlier.

RESTORERS OF THE WORLD

In 235AD, after over two centuries of uninterrupted internal peace, the Roman Emperor Severus Alexander was murdered by his Praetorian Guard while on campaign at modern day Mainz, Germany. What followed was a period of approximately 50 years in which 26 Emperors were recognized by the Senate in Rome, with countless others claiming the title. The Pax Romana was dead, and just like 24 of those 26 Emperors, it had been murdered by its own soldiers.

The period is called the Crisis of the Third Century, or the Military Anarchy. Rome was invaded by marauding barbarian armies, temporarily split into three competing states, and devastated by continuous vicious civil war and indiscriminate plague. In addition to severe population decline and general administrative collapse, the Roman economy, that chief determiner of prosperous societies, was crippled to a point where it would never fully recover. Trade between the urban centres dried up, cities walled themselves in to protect from marauding armies, and the Roman currency was heavily devalued to pay for soaring administrative and military costs, leading to ruinous hyperinflation.

In the year 267, much to the horror of the Romans, the Heruli and Gothic tribes managed to cross the Bosporus with a fleet and sack Athens, a dismaying example of the decline of Roman control over the frontiers. While they were eventually turned back by a Roman victory at Naissus, the attitude of the Romans had changed, and the future remained bleak for the Empire until 270AD. In that year, the Emperor Aurelian, soon to establish himself as a true military genius, defeat the barbarian tribes along the Rhine and Danube rivers, defeated Queen Zenobia, leader of the breakaway Palmyrene Empire in the east, and routed the armies of the breakaway Gallic Empire in the west. Aurelian’s stunning generalship led to the consolidation of all the Roman territories for the first time in nearly fifteen years. For this, he was awarded the title Restitutor Orbis – Restorer of the World.

Aurelian, brilliant though he was, fell victim to mutinous Praetorian troops like so many of his predecessors after four years of rule. He was eventually replaced by the Emperor Diocletian, who promptly made permanent Aurelian’s goal of unifying the Empire and ending the calamitous Crisis of the Third Century.

THE FOLLOWERS OF CHRIST

By the end of the Crisis of the Third Century, Christianity represented less than 10% of the population of the Roman Empire. The religion, which had only existed for around 250 years, was still relatively new. Although it grew steadily, the religion still remained a mainly underground movement as Roman policy towards Christianity oscillated between toleration and outright persecution.

Under Diocletian, Roman persecution of Christians reached a climax. From this era, came the bulk of the Christian martyrs still remembered today: St. George, and St. Sebastian among others. Most died between 300 and 305AD during the great attacks on early Christian society. In this period, we hear stories of Christians eaten by lions in front of cheering crowds at the Coliseum, along with mass public crucifixions. Property owned by Christians and Christian churches was confiscated by the Roman state, and their owners imprisoned, exiled, or executed. Rome was still Rome.

Diocletian himself promoted the traditional Roman pagan religion, emphasizing the deity Sol Invictus (Unconquerable Sun) made popular by Aurelian, and promoted himself as a divine subject, forever abandoning the humility shared by the early Emperors of the Principate.

It must be said, however, that the persecution was not popular with all Romans. In fact, in Diocletian’s day, Roman persecution of Christianity differed even between the co-emperors. In the west, the Emperor Constantius, for example, was not overly zealous in persecuting Christians, an attitude that would later be adopted by his son. In Rome, the sacrifice and bravery of the martyrs of the early Christian church did work to gradually draw attention and sympathy for the faithful. Eventually a respect grew among many Romans for the piety and selflessness of these early Christians.

THE FOUR PRINCES OF THE WORLD

Diocletian divided the administration of the Empire in two. While a linguistic division between the Latin-speaking west and Koine Greek-speaking east had existed since the days of the Republic, Diocletian’s decision to split the Empire was done for purely administrative reasons; it had become apparent that the Empire had become too large for one man, and one bureaucracy to control. Two Emperors, each called an ‘Augustus’ ruled two geographic halves of the Empire: One sat in Mediolanum, modern day Milan, and another in Nicomedia just outside modern Istanbul (at the time, a small Greek fishing and trading village called Byzantium), while the now powerless senate sat in Rome. It is important to note that, at this point and afterwards, these divisions were not seen as two separate states; there was only one Rome, and the division was purely to aid in the administration of the sprawling Empire. Diocletian ruled from Nicomedia over the richer, and more urban, eastern half of the Roman state, now comprising the Balkans, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt.

In 293AD, Diocletian divided the Empire once again, this time into four. There were not four Emperors, but rather two ‘Augusti’, and two ‘Caesars’, or junior emperors. An Augustus acted as a mentor to his junior emperors. This arrangement came to be known as the ‘Tetrarchy’, Greek for ‘Rule of Four’.

While the division of the Empire was intended to ease administrative efforts, and smooth out the succession process, while creating a balance of power between the corners of the Empire, it quickly devolved after Diocletian’s abdication and retirement in 305AD. Diocletian had for the duration of his reign controlled the primary military and economic components of the Empire, and when he abdicated after his imperial term had ended, his successor Emperors began to feud for total control of the Empire.

Diocletian promoted Galerius to Augustus in the East, and Maximin, Diocletian’s co-Emperor in the West, appointed Constantius as Augustus in the West. Furthermore, Maximinus was made Caesar in the East, and Severus in the West. Mutual suspicion plagued the relationships of the four Emperors. When Constantius, the Western Augustus died in in 306AD after just a year of rule, the Eastern Augustus Galerius who had taken over for Diocletian promoted the Western Caesar Severus as Augustus in his place. The transition process quickly broke down.

CONSTANTINE

Far to the north, in Eboracum (modern York, England), the son of the dead Augustus Constantius, a thirty four year old General named Constantine, camped with his legions. Left out of the line of succession by Galerius, Constantine, an able general and just leader, was soon declared Emperor by his troops. The acclamation of an Emperor by a distant army was all to familiar in the wake of the Crisis of the Third Century and now, under the rules of the Tetrarchy, posed a clear violation to the rules set down by Diocletian.

Constantine, still in his twenties, was a successful commander, and had established a devout loyalty from his soldiers. He had adopted a generally open-minded view on freedom of religion in the Empire from his father. Constantine was intelligent, learned, devious politically, and above all, ambitious.

In Nicomedia, Galerius heard the news of Constantine’s acclamation in a letter from Constantine himself. At first, the Emperor flew into a rage, but in a bid to avoid civil war he compromised with Constantine and offered him the lesser rank of Caesar, still insisting that his own candidate Severus remain Augustus of the West. Constantine accepted.

In a fateful nod to his third century predecessors, and encouraged by the success of Constantine, Maxentius, the son of the previous western Augustus Maximian, rebelled against Galerius and declared himself Emperor in Rome.

In alliance with Constantine, both Septimus Severus and Galerius rallied their legions and marched on Rome. Their forces were defeated in succession, and they were both forced to flee Italy. From Rome, Maxentius controlled most of the western Roman Empire, and had gained the support of the Senate. In order to secure his rule, Maxentius looked to normalize relations with Constantine, who still controlled the majority of Gaul (France), Britain, and the Rhine frontier. Soon, Constantine was married to Maxentius’ daughter, Fausta, and relations between the two had calmed to a manageable level.

However, the arrangement did not last, and within several years the growing power struggle between Constantine and Maxentius for control over the western half of the Empire was near breaking point. The conflict, maybe always inevitable, now erupted. As such, by Diocletians’s death in 311AD his political system had all but crumbled and had given way to a series of brutal civil wars.

IN THIS SIGN YOU SHALL CONQUER

Following a path very similar to that of Julius Caesar nearly 350 years beforehand, Constantine crossed the alps into northern Italy, and descended on the capital. His armies, veterans of the brutal Rhine frontier, won quick victories against Maxentius’ forces near modern Turin and Verona, and, having cleared the fertile Po river valley, crossed the Apennine mountains heading south into modern Tuscany and Lazio. By October 27, 312AD, Constantine’s army was camped just nine miles north of the city of Rome across the Tiber river, in a suburb called Prima Porta on the Via Flaminia highway.

In Rome that day, Maxentius held a chariot race at the Circus Maximus. Tensions across the Empire, and needless to say in the capital, reached a fever pitch as the armies of Constantine were reported to be just north of the eternal city. Maxentius, increasingly unpopular with the people, had the crowd turn on him at the games. They openly taunted the Emperor and chanted that Constantine’s advance could not be stopped. In a rage, Maxentius, along with his high priests, consulted the pagan Sibylline books, where it was determined that the next day, October 28th, ‘an enemy of Rome shall die’. Taking this prophesy as foretelling the death of Constantine, Maxentius, who had originally planned to stay inside the walls of the city and avoid battle, decided to join his army and march to engage Constantine outside the Aurelian Walls.

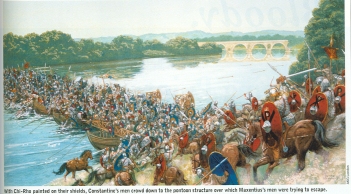

Now came the supreme moment. Camped in a field on the eve of battle, Constantine had a vision. There are two stories that report the incident. The earlier account claims that the vision came to Constantine in a dream in which the Greek letters Chi and Ro (the first two letters in the word Christ) superimposed upon each other appeared to him, and the second, recorded by the early Christian Historian Eusebius, claims that on the eve of battle Constantine saw a cross appear in the light of the sun. The words accompanying both images read (in Greek) ‘in this sign you shall conquer’. In any regard, Constantine, convinced he had been chosen as an instrument of the gods, commanded his troops, armed with the classical Roman pila (a short, weighted javelin), and the short Roman sword, to mark in white paint the Greek letters Chi and Ro on their round fourth-century shields (the Romans no longer used the rectangular shields employed in nearly every film adaptation of the period).

There is no consensus among historians as to whether or not the vision on the eve of battle signified Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. Some believe the event was simply a propaganda. It is true that Constantine was politically shrewd and devious, but it does not seem to make sense for him to use a conversion to Christianity to gain political support as at the time, maybe 10% of the Roman population was Christian.

Roman Emperors, after the turmoil of the third century, found their power not through politics in Rome, but through armies on the frontiers, and, on a fundamental level, Christianity was directly opposed to almost every value espoused by the Roman army. Christianity, particularly in this era where the teachings of Jesus were taken more literally than they were later on, espoused strictly pacifist ideology, and denounced the material and class-obsession of Greco-Roman paganism. It is most likely that Constantine truly believed he had been made into an instrument of the Christian god, in a very similar manner as had the Emperors of the third century in their relation to Sol Invictus, the Roman sun god. In this relationship, the Emperors paid homage to the gods for support in life and particularly, war.

THE BATTLE

In any case, at dawn on October 28th, 312AD, the two Roman armies faced each other across the Tiber river just north of Rome. Constantine’s army numbered nearly 100,000 men, while Maxentius’ forces were even larger. By numbers, it was in the realm of some of the largest Roman battles of all time: Cannae, Philippi, and the yet-to-be-fought Adrianople, and Chalons. Constantine’s forces, however, were composed almost entirely of veteran troops of the Rhine and Danube frontiers, experienced in combat against the Germanic barbarians to the north, while Maxentius’ troops were largely raw and untested.

Having ordered the destruction of all the bridges across the Tiber to delay Constantine’s advance on the capital, Maxentius ordered a temporary wooden pontoon bridge to be constructed just down river from the destroyed Milvian Bridge so so that his men might cross to engage Constantine on the north bank. Maxentius, eager now to fight and fulfill the Sibylline prophesy, formed up in a massive battle line with his back to the Tiber. Constantine, camped on the north side of the Tiber, the shields of his men emblazoned with the alien Chi-Rho symbol, engaged once Maxentius’ army had crossed the river. His battle-hardened veterans smashed the Maxentian vanguard, and through superior fighting quality, drove the Maxentius’ army into a retreat towards the river. As Maxentius’ formations shattered, the panic among his men grew. Upon finding their retreat blocked by the Tiber, all discipline shattered, and a free-for-all ensued. In a desperate plight to save their lives, the men of Maxentius’ routed army made for the pontoon bridge erected earlier that day.

Under the weight of his armoured troops, the bridge, already unstable, collapsed and threw hundreds of his frantic soldiers into the river. To fall into the river, given the weight of armour and the panicked mass of men, was a death sentence. The hope of making it across proved, however, more desirable than a brutal death at the hands of a veteran Roman army. Thousands drowned, and many more were cut down by Constantine’s pursuing army as they fled the battlefield. Caught in the crush, and forced towards the river in an attempt to save his own life, Maxentius drowned along with his men under the weight of full armour.

The next day, Constantine entered Rome as a victor, the shields of his men still marked with the Chi-Rho. He had conquered in the name of Christ.

MEDIOLANUM, NICAEA, AND CONSTANTINOPLE

After the conclusion of the civil war with Maxentius, Constantine, in conjunction with his new Eastern co-emperor Licinius, soon issued the Edict of Milan which allowed freedom of religion to all citizens of the Roman Empire. Although it was still not the official state religion, the Edict of Milan made Christianity a recognized religion from a legal standpoint. While Licinius tolerated Christianity in the east, Constantine began actively favoring it.

By 324AD, Constantine had finally overthrown his last opposition in Licinius at the Battle of Chrysopolis, and now held total dominion over the entire Roman world. A year later he called and presided over the Council of Nicaea, near Byzantium. The council called together the bishops of the Empire to discuss the early rifts which had already appeared in the church, particularly the early breakaway sects of the Donatists and Arians (named after the Bishop Arius, and not to be confused with the ethnic term ‘Aryans’). While Constantine held total control of the Roman armies and secular government, he was still not a bishop, and could not legislate on behalf of the church, a distinction continues to this day. In the end, while Constantine was unable to resolve both the Arian and Donatist disputes, the Council of Nicaea marked both the beginning of a clearly defined state religion (called Nicene Christianity), and the overlapping of state and church affairs.

In 330AD, the city of Constantinople (Greek for Constantine’s City) was founded at the site of an ancient Greek fishing colony called Byzantium. Constantine chose the site due to its strategic position between the Black and Mediterranean Seas, and as the link between Europe and Asia. Constantinople, as the new Eastern Roman capital, quickly became one of the most important cities in the world, and soon boasted a population of half a million residents, massive in those times. Constantine envisaged his city as a ‘New Rome’ – a spiritual replacement to the increasingly irrelevant city namesake of the Empire. While always being a government city (Like Ottawa or Washington), and not an economic capital in the later Roman world, Constantinople became the bulwark of Christianity. When the city finally fell to the Ottoman Emperor Mehmed II in 1453, the city held such a place in world history that the conquering Muslim Sultan called himself ‘Keysar-i Rum’, literally: Caesar of Rome.

Constantine was finally baptized shortly before his death in 337AD. While this is seen by a smaller fraction of historians as the date of his conversion, it is generally well understood that Constantine decided to put off his baptism until late in his life to avoid accumulating as much sin as possible during his reign.

Similarly, much debate continues around the time of Constantine’s conversion to christianity. Some historians claim Constantine became a christian upon his adoption of the Chi-Ro symbol on the eve of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, while others date the event to shortly before his death at the age of 65. Still others, being in minority, claim that he was never actually converted to christianity. Whatever the case, Constantine’s tolerance and favoritism of Christianity marked a paradigm shift in the western world.

In 380AD, the Emperor Theodoseus I declared Christianity as the official religion of the Roman state, and soon banned the practice of Roman paganism. Not until the modern age was true freedom of religion again offered the people.

A NEW ROME

With the gift of hindsight, it is generally understood that Christianity contributed to the collapse of the Roman Empire. However, when one considers the impact the Crisis of the Third Century had on the psyche of the Roman people, the rule of Constantine (and before him Diocletian) were seen as incredibly successful. To Romans, at the time of Constantine’s death the Empire had, for all intents and purposes, been restored. No one living in the age of Constantine could have foreseen that Rome would be sacked in eighty years, and that the empire would collapse in less than a hundred and fifty. Stability once again became the norm, inflation decreased, and trade slowly began to pick up.

Christianity, the favoured, and eventually adopted religion of the Emperors, was increasingly seen as a successful religion by hopeful Romans. Soon, the major urban centers, notably Rome, Carthage, Alexandria, Ephesus, Constantinople, and Antioch, were predominantly Christian. In the countryside, in the army, and among the scholars, the traditional Roman values and Roman paganism held out for some time, but eventually every citizen converted to the new religion. The spread was aided by several factors, including the growing apathy towards paganism, the promise of an afterlife in Christianity, and the success of its champions.

By the mid-fourth century AD, the new generation of Romans, already dulled by the indulgences of three centuries of internal peace, save the calamitous Crisis of the Third Century, found themselves suddenly shackled at birth to the docility and public sloth espoused so enthusiastically by the worshippers of the new religion. Suddenly, the great military traditions of honor, glory, ambition, and discipline, which were deeply ingrained in Greco-Roman polytheism, and which had upheld the quality and resolve of the fighting men that composed the legions of the Republic and Empire for a millennia, were cast aside by a sweeping philosophy that demanded chastity, piety, and peace.

The late Empire, already plagued by administrative and economic woes which might have proven insurmountable in their own right, found its young men, the future soldiers and administrators which had for so long preserved the integrity of Roman borders and institutions, choosing a life in the church over that in the army or government. The civil service soon fell into steep decline, the secular government became increasingly tied to the affairs of the church, and Emperors and governors became involved in the ecumenical arguments and schisms promoted by the early bishops that split the church and society in great theological debates.

As the young men of the empire became more deeply involved in church affairs as a career aspiration, the military establishment suffered, and enrollment of Roman troops declined at an alarming rate. By the late 300s, so sorry was the state of the old, Latin Romans, that imperial armies were frequently composed almost entirely of the barbarians they had fought against for a thousand years, now employed under promises of land within the relative safety of the empire’s borders (and far away from the ruthless and terrifying invasions of the Huns), plus massive government subsidies.

These barbarian mercenaries, filling in for the declining Italian Roman soldiers and officers, increasingly diluted not only the army, but the administration as well, particularly in the west, where their devious and impetuous influence, obsession with he personal accumulation of wealth and power, and resultant disinterest in the public institutions and services of the Empire, worked only to further destabilize the declining empire. With no reason for personal loyalty to the Roman state, barbarians made their way into the channels of power, and used those officers for their own personal benefit at the expense of the government and people of the empire. By 476AD, the Western Roman Empire had entirely collapsed.

Ultimately, the Battle of the Milvian Bridge changed the history of Europe, and with it, the entire world. Constantine’s decisive victory on the Tiber began the process that turned Rome, the greatest nation in history, into a Christian nation, and at the same time sewed the seeds of its eventual collapse.

Thank you for reading.